Modern Perspectives on Childhood Obesity – Dr. Narmin Azizova

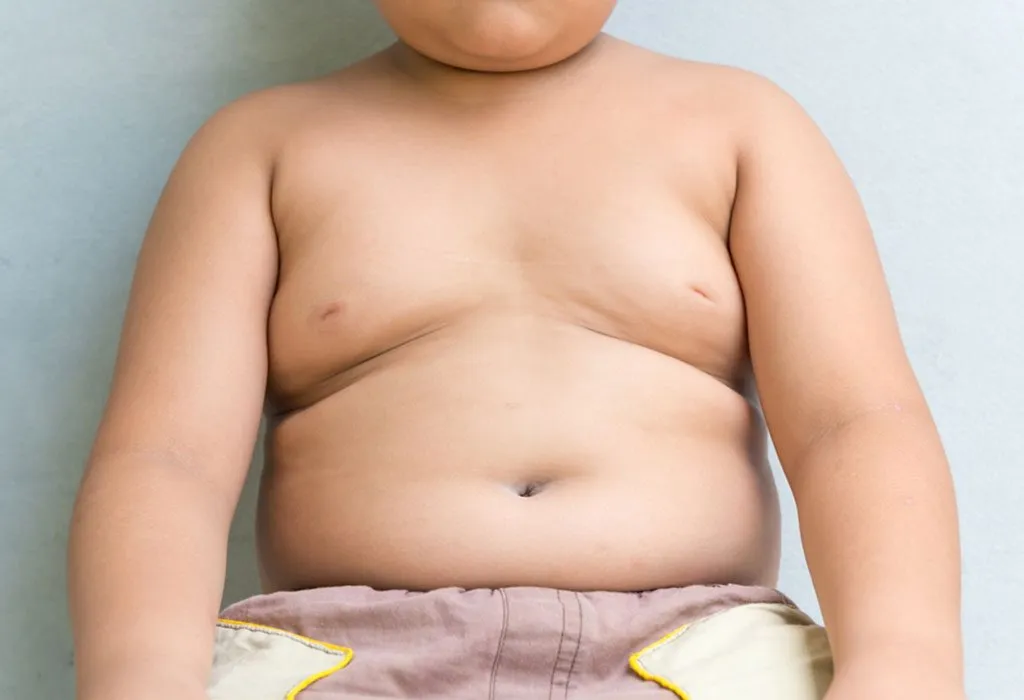

Obesity, or being overweight, is a condition characterized by an excessive accumulation of fat in the body, which results in a disruption of energy metabolism. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines obesity as a health problem arising when the intake of energy exceeds the body’s energy expenditure, leading to the accumulation of fat tissue in various parts of the body.

Over the past 40 years, there has been a phenomenal increase in childhood obesity rates in developed countries. According to the WHO, by 2010, 43 million children under the age of 5 were classified as overweight. Among them, 35 million live in developing countries. When comparing this statistic with that of the 1990s, a 4.2% increase in obesity rates is notable. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies obesity as having a body mass index (BMI) greater than the 95th percentile for age and sex, while children with a BMI between the 85th and 95th percentiles are considered at risk for obesity.

Causes of Obesity in Childhood:

The mechanism of obesity is not fully understood, but it is believed to be caused by a combination of factors. Childhood obesity can be classified into two types: simple (exogenous) and secondary obesity.

Differential Diagnosis of Childhood Obesity:

| Simple Obesity | Secondary Obesity |

| Family history: Positive | Family history: Negative |

| Height: Tall (>50th percentile) | Height: Short |

| Intellectual development: Normal | Intellectual development: Generally low |

| Bone age: Normal | Bone age: Delayed |

| Physical examination: Normal | Physical examination: Pathological signs (+) |

Simple obesity (exogenous obesity) occurs in children without any underlying disease. Children with this type tend to have a good appetite and a preference for sugary, fatty, and processed foods. Inconsistent eating habits, such as eating too quickly or consuming large quantities of food, can contribute to rapid obesity development. This leads to the development of a hyperplastic form of obesity, where the number of fat cells increases.

Secondary obesity, on the other hand, may be linked to endocrine factors such as hypothalamic pathologies, Cushing’s disease, hypothyroidism, growth hormone deficiency, pseudohypoparathyroidism, insulinoma, hyperinsulinemia, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and hypogonadal syndromes. Genetic syndromes, including Alström syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, Cohen syndrome, Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and Carpenter syndrome, can also contribute to the development of secondary obesity. Additionally, long-term use of certain medications, such as glucocorticoids, tricyclic antidepressants, anti-thyroid drugs, estrogen, progesterone, lithium, phenothiazines, and cyproheptadine, may lead to obesity.

Factors Influencing the Development of Obesity in Children:

Genetic factors play a significant role in the development of obesity. Some studies have shown that 25-40% of a child’s BMI may be influenced by genetic factors. If both parents are obese, there is an 80% chance their child will also be obese; if only one parent is obese, the risk is 40-50%; and if neither parent is obese, the risk is 7-9%. However, environmental and behavioral factors also play a crucial role in the development of obesity, making it clear that genetics alone is not the sole cause.

The biological disturbances associated with obesity are thought to be related to mechanisms that regulate energy balance in the hypothalamus. Specific genetic defects, such as those involving the leptin gene, have been linked to obesity. Leptin, a hormone produced by adipose tissue, regulates fat and carbohydrate metabolism and appetite. When leptin levels decrease, hunger increases, and when food intake is excessive, leptin levels rise.

Obesity can occur at any age, but certain periods in childhood are considered higher-risk. The first critical risk period is between 6-12 months of age, the second is between 4-6 years, and the third is during puberty. The period from 5 years of age onward is particularly important as the BMI increases, a phenomenon known as “adiposity rebound.” During adolescence, girls tend to accumulate fat in their thighs and buttocks, while boys experience fat accumulation in the abdominal region.

A lack of physical activity and sedentary behavior, such as excessive screen time, are major contributors to childhood obesity. Research has shown that the risk of obesity is higher in children who watch television for more than 4 hours a day compared to those who watch less.

Psychological Factors and Obesity:

Psychological factors, including family dynamics and school environment, can also contribute to childhood obesity. Negative relationships between parents and children can lead to emotional eating and a preference for high-calorie comfort foods. This can, in turn, affect a child’s academic performance, social life, and overall behavior, leading to further weight gain.

Assessment of Obesity:

Various laboratory methods can be used to measure body fat:

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Anthropometric measurements | Quick, simple, and inexpensive; widely used in population studies | Varies by age and sex |

| Bioelectrical impedance analysis | Fast, simple, and inexpensive | Affected by hydration status |

| Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) | Quick and simple; provides information about fat distribution | Expensive, insufficient for separating subcutaneous and visceral fat |

| Ultrasound | Measures subcutaneous fat and muscle tissue | Lack of sufficient experience |

| Computed tomography (CT) and Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | Can measure specific anatomical sites | Expensive and involves radiation (CT) |

Clinically, indirect anthropometric measurements such as BMI, relative weight, skinfold thickness, and waist-to-hip ratio are commonly used. However, BMI may not be suitable for children as it does not differentiate between fat and lean tissue. Therefore, percentile and z-score values are often used to assess growth and weight status in children. The WHO provides growth standards for children aged 0-5 years (2006) and references for children aged 5-19 years (2007).

Complications of Obesity:

Childhood obesity significantly increases the risk of Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and other health issues. Obese children often exhibit lipid imbalances, with elevated total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides, and decreased HDL cholesterol. Respiratory issues, particularly sleep apnea, are common, and osteoarthritis is also frequently seen in obese children. Other complications include gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD), musculoskeletal problems, and increased susceptibility to infections due to excess subcutaneous fat.

Psychosocial Issues in Obese Children:

Obese children often experience delayed physical development and may suffer from psychological issues such as low self-esteem, body image disorders, and social isolation. In severe cases, obesity may lead to eating disorders or depression.

Treatment and Prevention of Childhood Obesity:

The goal in managing obesity in childhood and adolescence is not only to reduce weight but also to establish healthy eating habits and promote regular physical activity. For children aged 2-5 years, weight loss should be gradual, aiming for approximately 500 grams per month. For children aged 6-18 years, the goal should be around 1 kg per week.

For children with mild obesity, adjusting their diet and increasing physical activity may be sufficient. In cases of severe obesity (BMI >40), a more structured approach involving a reduction in calorie intake by 10-20% for 6-8 weeks may be necessary. If serious complications, such as hypertension, diabetes, or sleep apnea, are present, a very low-calorie diet (10-15 kcal/kg/day) may be required, followed by a protein-modified diet.

In addition to dietary changes, regular physical activity is essential. The WHO recommends that children aged 5-17 engage in at least 60 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity every day.

The daily calorie intake for obese children should be tailored according to their age and weight goals. Regular follow-up and monitoring are crucial for long-term success in managing childhood obesity.

Conclusion:

Prevention and treatment of childhood obesity require a multifaceted approach that includes balanced nutrition, physical activity, and psychological support. Encouraging healthy habits early on and providing support for both children and their families can help combat this growing epidemic and ensure better health outcomes in the future.